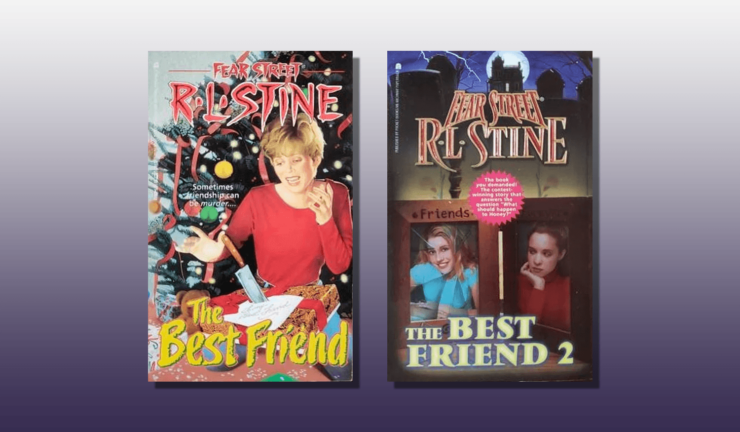

Friendship is a risky business in ‘90s teen horror. There are friends who have your back, no matter what supernatural threat or knife-wielding maniac is lurking just around the corner, and those who would shove you in front of the monster, then step over your dead body to steal your boyfriend. New friends might be mysterious but oddly trustworthy, while your oldest friends might be the ones who betray you. R.L. Stine’s Fear Street books The Best Friend (1992) and The Best Friend 2 (1997) explore the darker side of friendship, when “best friends forever” becomes a curse rather than a comfort.

The Best Friend starts with an odd mystery: Becka Norwood is hanging out in her room with her friends Trish Walters and Lilah Brewer, when a girl bursts in, exclaiming “Becka! Becka! I’m so happy to see you!” (13). This mystery girl introduces herself as Honey Perkins and, overcome with emotion, tells Becka they were best friends in the fourth grade before Honey and her family moved away, but now Honey and her father are back, moving into the house next door, and Honey can’t wait to pick up their friendship right where they left off. But the thing is that Becka has absolutely no memory of this girl. Honey only has eyes for Becka and completely ignores Trish and Lila when they try to talk to Honey, introduce themselves, or ask her about herself and her family.

And it only gets weirder from there: Honey lets herself into Becka’s house when no one’s home and goes through Becka’s closet, trying on all of her clothes. She steals a piece of jewelry from Becka and when Becka confronts her, insists that Becka gave it to her as a present. She cuts her hair exactly like Becka’s and makes out with Becka’s ex-boyfriend. When Becka stays home sick one day, Honey tells everyone in school that Becka had a mental breakdown. She shows up at Becka’s house every morning to walk with her to school and calls her several times every night. She chokes Becka and when Becka is (understandably) horrified, Honey gets all sad and pouty, saying “don’t you remember the Gotcha game? … We used to do the worst things to each other … We always thought that Gotcha game was a riot. You remember—don’t you, Becka?” (42-43, emphasis original).

Buy the Book

Nestlings

Honey is jealous of Becka’s other friends and when Trish and Lilah take up too much of Becka’s time and attention, they start to have “accidents.” Becka and Lilah go for a bike ride after school one day. Honey doesn’t have a bike and can’t come along, and they’re enjoying a pleasant Honey-less afternoon right up until they discover that Lilah’s brakes have been tampered with and she gets HIT BY A TRUCK. Lilah is in a coma for a few days and nearly dies (though she eventually ends up making a full recovery). Honey isn’t invited to Trish’s Christmas party, but she shows up anyway, dressed in the exact same outfit as Becka, yelling “hiya, twin!” (120), and when Becka tells her to go away, Honey pushes Trish down the stairs and breaks her neck (though Trish also eventually ends up making a full recovery). Honey rats out Becka to her mom when Becka sneaks out to see Bill, a boy Becka’s parents don’t approve of, to make it harder for Becka and Bill to see one another. Once she has driven this wedge between Becka and Bill, Honey invites Bill over to her house, stabs him, and frames Becka.

If Honey’s obsession and active campaign to destroy Becka’s life isn’t terrifying enough, there’s also the fact that NO ONE believes Becka. Becka has a reputation for being a little tightly-wound, a bit dramatic, and prone to stressing out over every little thing. Becka’s friends, boyfriend, and mother all repeatedly tell Becka that she’s overreacting, that she’s not being fair to Honey, and that if Becka’s just a little nicer and has a bit of patience with Honey, that everything will be okay. Honey will settle in and make new friends, which will temper the intensity of her focus on and relationship with Becka. Trish tells Becka that she needs to “calm down” and “just chill” (90). Bill tells Becka that “maybe you are being a little unfair to Honey … Honey isn’t that bad. In fact, she’s kind of cute” (104). Becka is terrified, occasionally hysterical, and completely alone.

Honey gaslights Becka throughout the book, telling her about all of the fun times they used to have and all the things they used to do together, though Becka still can’t remember any of these things and frankly, many of them seem pretty implausible, like when Honey tells Becka that the two of them used to shoot each other with squirt guns during class and “we’d be totally soaked by the end of the day, remember?” (99). Becka is constantly off-balance, trying to figure out which things may have actually happened, whether she’s forgotten a whole section of her childhood or if Honey is trying to convince her of a past—and a relationship—that never actually existed. When Becka refutes Honey’s memories, telling her that these things never happened, Honey remains insistent, telling Becka “you just don’t remember” (99). Becka is able to hold on to the memories she knows to be true, trust her intuition, and resist Honey’s version of events, though in the final scene of The Best Friend, Honey is finally able to remake Becka’s reality just the way she wants to: when Becka and Honey get in a fight, Becka faints, and Bill tries to intervene, Honey screams at him to “stay away! She’s my friend. My best friend” (144, emphasis original), and then stabs Bill in the chest. Honey puts the knife in Becka’s hand and as Becka begins to regain consciousness, Honey tells her “I’ll take care of you, Becka. I’m your only friend now” (146). While Becka has been able to resist Honey’s version of the truth up to this point, between the bump on her head and waking up to find that it looks like she murdered someone, Honey finally wins.

Well, Stine’s readers did NOT like that. As Stine writes in a “Dear Reader” introduction to The Best Friend 2, “hundreds of you wrote to tell me how unhappy you were with the ending. You thought Honey Perkins should pay for her crimes.” There’s a lot to unpack here, including the fact that a large number of fans were apparently so invested in the series that they felt compelled to write to Stine (or that, if this was a marketing ploy, it would be a believable one), which seems to belie the perception that these books, which were flooding the teen fiction market at the time, were inconsequential, low-impact, and disposable entertainment. Also, these teen readers were apparently driven by moral outrage, the belief that the world should be fair and that the bad should be punished. They wanted to restore order, to see justice—or at least vengeance—served, firm believers in the value and rightness of the status quo. Even more interesting was Stine’s willingness to cede some of this power to his readers. When the time came for The Best Friend 2, Stine didn’t simply write the sequel—he held a contest for readers to send him their plot suggestions for what they thought ought to happen next and what should happen to Honey. Thousands of readers sent in their ideas, with the winning entry submitted by Sara Bikman from Grafton, Wisconsin, and a caption on the cover identifying The Best Friend 2 as “the book you demanded.” The interaction between Stine, his work, and his fans here is interesting, and the way in which he invited readers to participate in telling the story and impacting the outcome may have been gimmicky, but it was also a couple of decades ahead of innovative participatory story-telling we now see across multimedia platforms.

The Best Friend 2 is divided into three parts and in Part One, I was actually really worried about Becka, who was getting a fresh start at Waynesbridge High School after surviving the events of the previous winter. Becka is the first-person narrator of this opening section, trying to hold it together and not really doing a great job of it. She keeps hysterically running up to random guys and hugging them, believing they are Bill, back from the dead. She has imaginary phone conversations where a cute boy from her new school tells her how much he likes her. And when she makes a new friend, Glynis, Becka buys the same color nail polish, gets her hair cut the same way, and tries on Glynis’s clothes and borrows them without asking, reassuring herself that “why should she mind? Best friends always borrow each other’s clothes. That’s what best friends do” (37). In trying to get a fresh start after Honey, Becka seems to lack the self-awareness to realize that she is doing many of the same unsettling, obsessive, and boundary-crossing things that Honey did to her not that long ago. While this could give us an opportunity to explore the behavioral aftermath of trauma or give Becka an admittedly problematic chance to empathize with Honey, we end up not having to worry about any of that, because this “Becka” is ACTUALLY HONEY. After the events in the final chapter of The Best Friend, apparently the truth came out and Honey was institutionalized, but she broke out, made her way back toward Shadyside, then forged a bunch of official documents, stole Becka’s identity, and enrolled in high school in nearby Waynesbridge.

Honey honestly believes that she is Becka and when she comes face to face with the real Becka at the mall in Shadyside and this illusion is shattered, she murders a boy right in the middle of a store, in front of a bunch of witnesses, then screams at everyone that the other Becka did it and runs away, escaping once again. The second part of the book then picks up the real Becka’s story, filling readers in on how she put the pieces back together and attempted to get on with her life after Hurricane Honey. While the “Becka” of Part One has been unmasked, Becka and Honey’s perceptions still share some notable similarities, highlighting the trauma Becka has survived. Like Becka/Honey, real Becka also frequently thinks she sees someone who isn’t there, in this case, seeing Honey’s face in the crowd rather than Bill’s. She’s jumpy and paranoid (though really, who can blame her, especially once she knows Honey’s back?). It turns out that Bill survived Honey’s attack, though Becka won’t talk to him, refusing to reopen the door to those terrifying memories, no matter how angry or insistent Bill becomes. Real Becka isn’t doing quite as badly as Becka/Honey, but she’s not doing great. And she starts doing a lot worse when Honey begins threatening her and stalking her, then finally attacks and nearly kills Becka outside her psychiatrist’s office.

While in some ways, the story picks up right where it left off, there’s a lot that’s left out. Trisha and Lilah are both recovered from their injuries, and while we know that the rehabilitation took a long time and was difficult, that’s all we know. There are no scenes of support or healing, rebuilding friendships, progress and setbacks. Similarly, we’re not 100% sure how everything got sorted out with the Becka/Honey/Bill situation at the end of The Best Friend. Becka’s name was cleared and Honey was identified as the actual attacker, but how? Did Becka remember what happened and clear her own name? Did Bill save the day and tell everyone what really happened (and if that’s the case, do we feel differently about how Becka is treating Bill now)? Were the Shadyside cops particularly insightful and astute this time around? In each of these cases, these processes are transformative for those involved, changing who they are and how they see the world around them (sometimes—as we will see—with disastrous results), but the details themselves are unclear.

The Best Friend 2 also revises and reframes part of the core narrative of the first book, when Lilah digs up an old newspaper article that reveals that Honey isn’t really Honey … or at least, that hasn’t always been her name. It turns out that all of the girls actually did know each other, though their relationship and memories of one another are vastly different than Honey had claimed. When the girls were all in fourth grade together, her name was Hannah Paulsen and she desperately wanted to be friends with them. The girls played an “unbelievably cruel trick” (96) on her, telling Hannah that she could be their friend and be part of the Cool Club if she got up on the stage during an all-school assembly, got down on all fours, and barked like a dog. She did and then they told her there actually was no Cool Club and she still couldn’t be their friend, along with the hope that “maybe you’ll stop following us around like a puppy” (97). Shortly after that, Hannah disappeared and it’s not until Lilah finds an old newspaper article that they find out that Hannah was the only survivor when her father killed her brother and mother, then himself (whether or not this is exactly what happened remains a thought-provoking but unanswered question). The man they know as Honey’s father is actually her uncle, Honey is Hannah, and her motivation for tormenting Becka makes more sense now. It’s a complicated amalgamation of rejection, wish fulfillment, and vengeance, as Honey creates a fictional past in which she had the best friend she always wanted, while simultaneously punishing Becka’s failure to be that person when they were children, as Honey repays Becka’s cruelty with her own.

But just when we think we have Honey figured out and know what she’s capable of … it turns out we’re wrong. Again. Because some of the stuff that Honey has been doing to scare Becka in the last third or so of the book wasn’t actually Honey at all, because Honey was arrested and is back in custody. When “Honey” calls to tell Becka she’s coming to kill her, Bill miraculously shows up in Becka’s driveway, telling her that he’ll be happy to take her to “my uncle’s cabin back in the Fear Street Woods … You’ll be safe there” (136). Nothing about that sentence makes any sense, but Becka is desperate and terrified so she goes along with it, falling right into a trap set by Bill and Trish. Becka has always known that Honey was most definitely not her best friend, but it never crossed her mind to doubt the solidity and support of her friendship with Trish. However, Trish has been harboring hatred and resentment toward Becka since Honey pushed her down the stairs at her Christmas party, particularly because Becka was rarely there for her during her long and painful recovery. As Trisha tells Becka when she confronts her in the cabin, “you hardly came to see me at all … You couldn’t because you were so wrapped up in yourself. You only cared about taking care of yourself, Becka” (144). And to be honest, Trish has a point—Becka can be pretty self-absorbed and has trouble seeing things from other people’s perspectives. But she had also just survived something pretty horrific and was doing some serious healing of her own. While Trish sees Becka’s absence as a betrayal, her demand could also easily be read as a toxic definition of friendship, in which she is demanding that her friend sacrifice her own well-being to be there for her instead. It’s definitely complicated. When Trish goes to stab Becka, Bill jumps in front of the knife and ends up stabbed in the chest AGAIN (poor Bill!), hopefully on the same side as last time, because the guy is already down to one lung. Becka disarms Trish and takes Bill’s hand, promising that this time “I’ll be a good friend” (148), which feels like a tacked on and not particularly resonant lesson.

There are very few examples of authentic friendship in these two books: Becka and her friends tormented and tricked Hannah, which set her plan for vengeance into motion. Becka is a bit self-absorbed, rarely sparing a thought for friends like Trish and Lilah, even when they really need her. Bill wants Becka to hear him out throughout Best Friend 2, often resorting to angry outbursts and emotional manipulation in an attempt to get her to give him a chance. Honey is the most violent and problematic of the false friends in these two books, but she’s definitely not the only one. In the end, Lilah is the only one who stays true and reliable, having patience with Becka but also holding her accountable when she goes too far, and calling to make sure Becka got to that super safe cabin in the Fear Street Woods okay.

Stine’s The Best Friend and The Best Friend 2 are a wild ride. Becka has a stalker who claims to be her best friend, but in the end, even her actual best friend wants to murder her. Reality and perception are frequently amorphous, as Becka’s perceptions of what’s going on often fail to match up with anyone else’s, whether it’s the memories Honey tells her she ought to have or the friends and family who tell her she’s overreacting. Honey isn’t even Honey and no matter how much she wants it to be true in the first section of The Best Friend 2, she’s definitely not Becka. At the end of The Best Friend 2, Becka promises Bill that she’s going to mend her ways and be a better friend to him, though it’s hard to imagine her trusting anyone again any time soon.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.